群展 瓦尔德伯格·沃特斯画廊,布鲁塞尔,比利时

“Abstract Painting” is a contradiction in terms, a lazy misnomer. There is nothing abstract about painting. My attempt at a physical definition of painting: the application by a person of hue to a surface. This happens in the real world. The person is possibly an artist, self-described or otherwise. Everything else is widely cast.

The point about the word “abstract” was its non-objectivity. Abstract pictures were not meant to be about a subject—a tree, a god, a soup can—but their own painting—their own physicality. This more or less we have from Clement Greenberg and latterly Michael Fried. The subject has proved surprisingly durable but it becomes solipsistic. A hundred years after Malevich painted “Black Square” (1915, oil on canvas, 79.5 x 79.5 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) we are still looking for the subject. This I suggest is the real subject: the search for meaning and the reinvention of what we take for meaning. The answer is irrelevant.

One of the intellectual engines of art in China in the past 20 years was a small, diverse group of artists in Shanghai, of different ages, backgrounds and provinces. It included Ding Yi (b. 1962), Zhang Enli (b. 1965), Zhou Tiehai (b.1966), and latterly Xu Zhen (b. 1977). If we look at these four artists, their styles and approaches to art are quite different. In this exhibition we have an opportunity to compare the oldest and youngest of the four with regard to their recent (relatively) small-scale abstract works. They are interesting because they address the issue of painting from opposite directions and yet meet at a certain point.

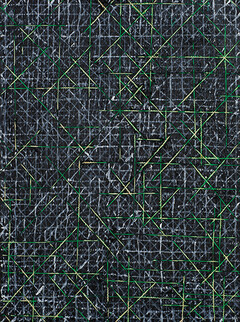

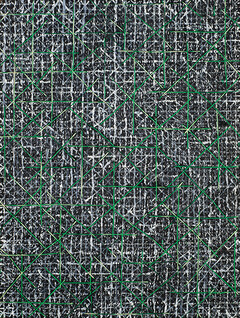

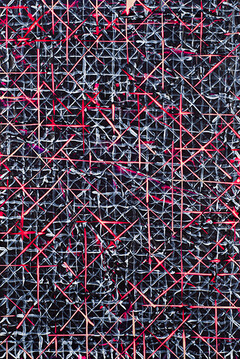

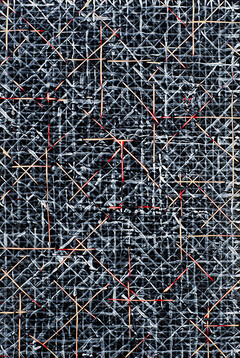

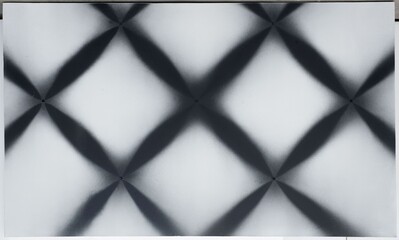

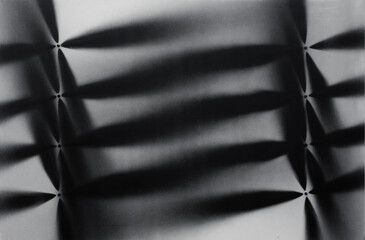

Ding Yi has long practiced a painstaking painting technique that composes images from a mass of meticulous crosses— “x” and “+”—of different colors. The apparent subject is the crosses and their making: large canvases take months to finish. The paintings respond to both traditional Chinese painting techniques rooted in the culture of Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism. To dwell on this though is to miss what is in front of us: many, many crosses. They both mark and efface a point. They confirm and deny. They are multiples and additions of themselves—sums without numbers. At times they shimmer, hovering above the picture plane, particularly in the works made on tartan cloth. At other times they induce a sense of nausea, of airlessness. They are barriers to and systems of communication.

In these new small works however, the lines that make the crosses have become trailing, linking up and running off into other crosses. The black space they cross over remains unreachable but it does not matter—the web of lines is absorbing enough. They are small windows (not keys) into the worlds of the older, bigger canvases, worlds created precisely not to be explicated. They are intended to remain abstract realities, foreign bodies. They represent themselves, even while another reality, the reality of their making, exists transmutably within Ding Yi himself.

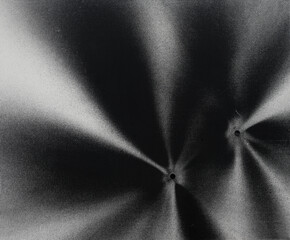

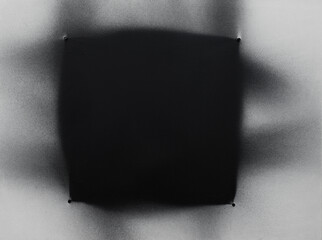

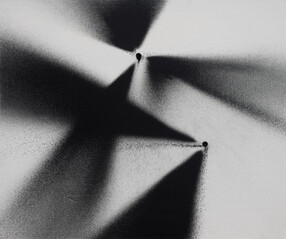

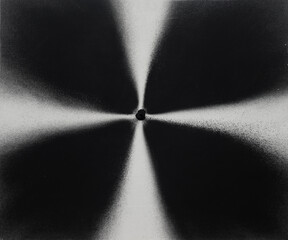

Meanwhile Xu Zhen, a conceptual artist who has experimented on and off with abstract painting for almost ten years, has caused to be created under his brand of MadeIn a series of paintings called “Turbulent”. These were first created and exhibited in Shanghai at Bund 18 Temporary Art Space in a show curated by Li Zhenhua. Each painting experiments with a black abstract form created with a spray can directed from set points. Some resemble a mesh fence or a rotating fan or blade or even certain early Constructivist and Surrealist experiments with photography. The turbulence is the spray of paint from the nozzle of the can and, maybe, the time in which it is made. Its point is that it is pointless. The action of the “action painting” is empty. The turbulence is dumb. The sound and the fury is air bisected by minute drops of ink propelled through space onto a surface. Is it just decoration or part of the growing abstraction lexicon, or both?

The issue with both Ding Yi and Xu Zhen is the uncertainty of abstraction. Whereas Ding Yi uses it as a shield and a statement of self, a refusal to explain, Xu Zhen uses it to question its relationship to people, how we judge it and fail— inevitably and rightly— to judge it.

The reason abstraction remains a fascinating conundrum is because it is a mirror. In Ding Yi’s paintings it faces towards himself. In Xu Zhen’s it is turned upon us.

written by Chris Moore

More Pictures: